“. . .a shared women’s intimacy.”

In honor of all us imperfect mothers…

I back through the door of the ladies room

pulling stroller, wailing baby, all his gear

(not a graceful entrance) into the anteroom

adjacent to wash basins and toilet stalls.

I gather his indignant, thrashing form,

my impatience nearly matching his,

and perch on the cracked Naugahyde settee.

Dammit. What bad timing. This twenty minutes

means rush hour traffic going home.

I sling a receiving blanket over my shoulder,

and squalls turn to contented gurgles.

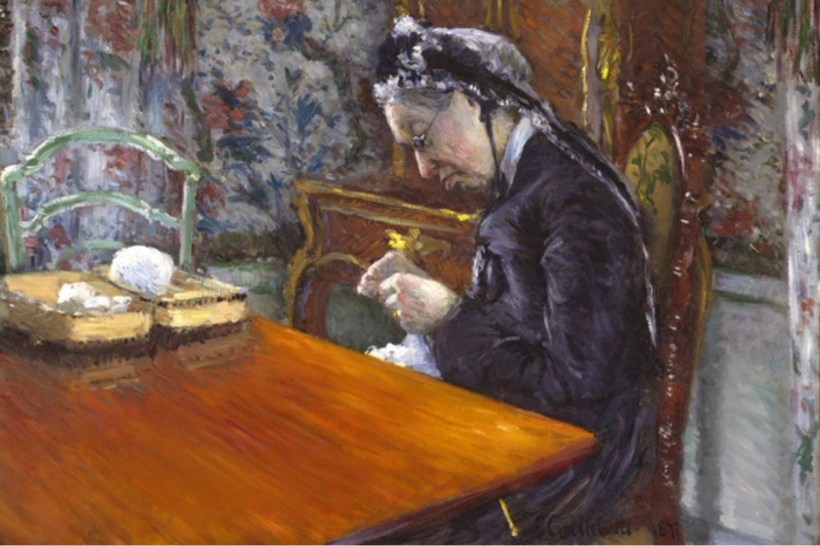

Only then do I notice the frail, ancient figure

in a chair nearby, her cane leaned carefully beside her.

I smile, apologetic for intrusion, her catching me

at not-my-best-mom self, my feeling

of nakedness under the scrap of flannel.

Her face is soft with wrinkles and surprise.

“Oh my, you’re nursing your baby,” she says.

“I didn’t think girls did that anymore.”

I tell her it’s become the norm,

that studies show it’s healthier.

“Do you mind if I sit here with you?” she asks.

I assure her it will be all right.

We are alone, the restroom quiet

on a Tuesday afternoon,

save for soothing baby sounds.

I relax, change sides, let the blanket slip

in a shared women’s intimacy.

Finally the baby breaks away, eyes closed,

still suckling in his sleep. “I nursed seven babies,”

she tells me then. “If I close my eyes,

I almost remember what it feels like,

having a baby at my breast.”

I can’t speak, overwhelmed

by the miracle of milk.

– Sarah Russell

First published in The Houseboat